EBITDA margin is a popular term but it can't be found on any financial statement. It has to be calculated and is a great way for owners to see how much cash their company has brought in. In this post, we are going to answer the many questions surrounding this important financial indicator:

- What is EBITDA Margin?

- How to Calculate EBITDA

- How is EBITDA used in Business Valuation?

- Why are Interest, Depreciation, and Amortization Added Back in EBITDA?

- Does EBITDA include CapEx?

- Is EBIT or EBITDA Better?

- What is an EBITDA Bridge?

What is EBITDA Margin?

First of all, EBITDA is an acronym that stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Deprecation, and Amortization.

Simply put, EBITDA margin is a company’s operating profit as a percentage of its total revenue that allows investors to compare a company’s financial performance to others in the industry according to Investopedia.

Calculating EBITDA is an excellent shorthand way to determine how much cash a company has generated from its business operations.

This is significant because cash generated from operations is the primary driver of business valuation.

How to Calculate EBITDA

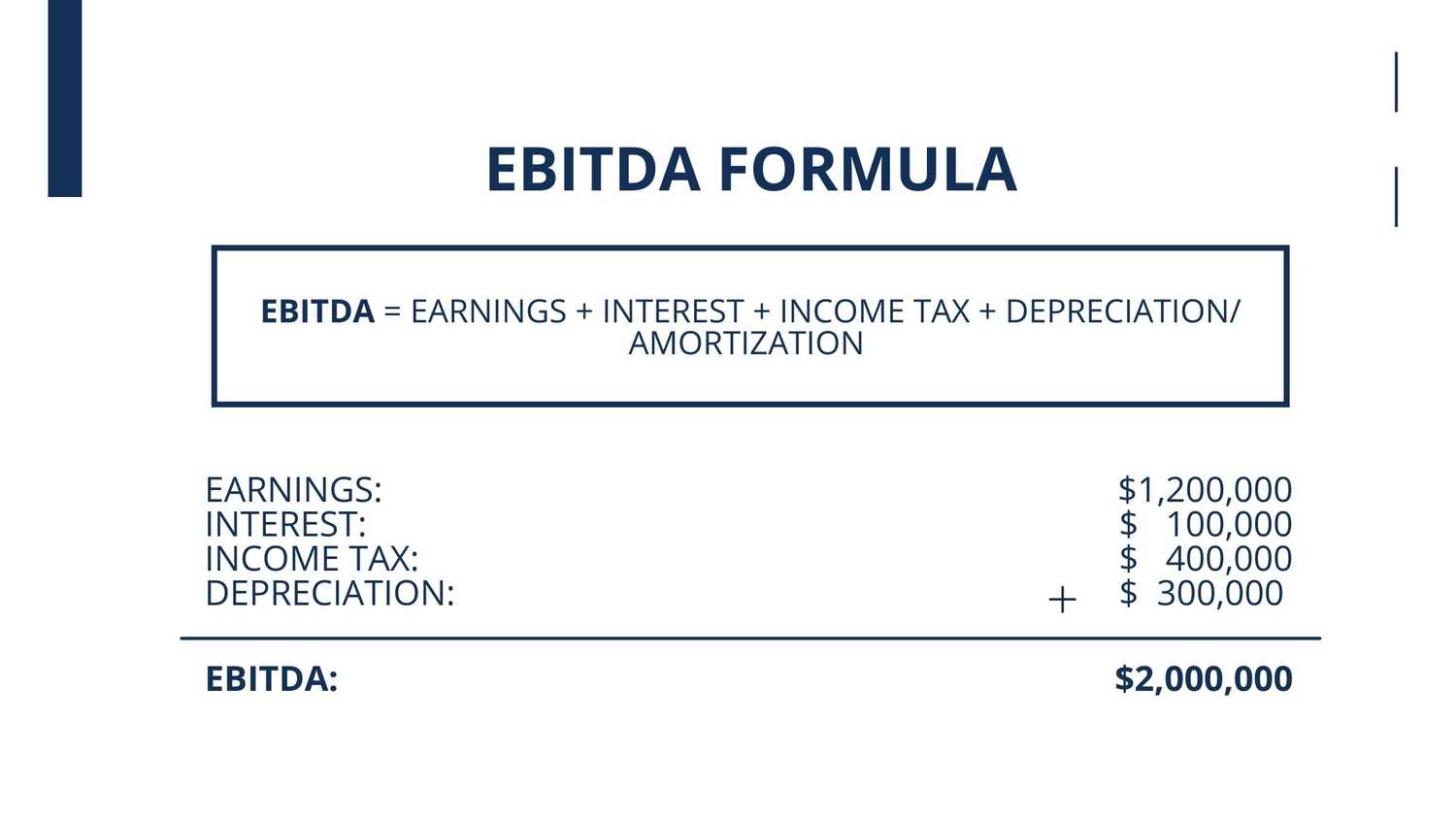

To calculate EBITDA, simply take the net income (Earnings) shown at the bottom of any income statement and add to it any interest, income tax, depreciation, and/or amortization expenses also shown on that income statement.

The result is EBITDA.

For instance, consider a manufacturer with $10 million of revenue, $4 million of gross profit, and $1.2 million of net income (earnings).

If this manufacturer’s expenses as shown on its income statement were to include $100,000 of interest expense, $400,000 of income taxes ,and $300,000 of depreciation, its EBITDA would be $2.0 million and its EBITDA margin would be 20%.

Watch the video below for another example:

How Is EBITDA Used in Business Valuation?

To determine a company’s EBITDA valuation, we take its recent annual EBITDA (or its EBITDA less Capex or EBIT, as the case may be) and multiply it by a figure (a ‘multiple’), typically between 4 and 5.

The multiple we use is dependent on the past and likely future consistency of a company’s EBITDA and its potential to grow over time.

For instance, a company that has just a few customers and sees its EBITDA go up and down wildly from year to year would result in a low multiple (maybe 2-4x), while a company with a very steady and growing EBITDA would attract a higher multiple (5x, or more).

Other factors that impact the EBITDA multiple include the size of a company (bigger is better), its EBITDA margin (typically, investors such as Hadley Capital want to see EBITDA margins in excess of 10%), and the amount of capital expenditures required to maintain and grow the company.

Why are Interest, Depreciation, and Amortization Added Back in EBITDA?

Why do we add-back interest?

The interest expense a company pays is dependent on how much debt it has.

If a business has a lot of debt, then it will have a lot of interest expense. The identical business without any debt will have zero interest expense.

Because the debt structure of a company is not related to how much cash its operations generate (only where that cash goes) interest is added back in the EBITDA formula.

The amount of income tax expense a company pays is, like debt, highly dependent on items such as its corporate form (S Corp v. C Corp), accounting practices, the amount of debt it has, and other factors not in any way related to its operating performance.

This is why income taxes are also added back to the EBITDA formula.

Depreciation and Amortization are added back in the calculation of EBITDA because they are non-cash charges against earnings.

Depreciation reflects the declining value of a tangible asset (like a piece of equipment) as it wears out or becomes obsolete, while Amortization reflects the declining value of an intangible asset (like a patent) as its useful life declines.

The accounting treatment of depreciation and amortization rarely reflect the real "costs" associated with acquiring/owning these assets and, since they are non-cash charges, adding back depreciation and amortization better reflects current-period cash flows.

Does EBITDA include CapEx?

Another common question that comes up when calculating EBITDA is if capital expenditures are included.

The short answer is no and here’s why: there is one important caveat related to depreciation. Buying tangible assets (like equipment) is a real cash cost (typically referred to as capital expenditures or ‘CapEx').

CapEx shows up on the balance sheet in the form of additional fixed assets instead of the income statement as an expense.

As a result, we often refer to a company's 'EBITDA less CapEx' instead of just its EBITDA, or we might instead refer to that company’s EBIT, which is just its EBITDA without the depreciation and amortization add-backs.

Is EBIT or EBITDA Better?

Hadley Capital typically uses EBIT as the primary proxy for a company’s cash flow when that company has lots of recurring capital expenditures, such as one that uses lots of vehicles or which needs to buy new equipment every few years to stay competitive in its industry.

In doing so, we assume that the company’s depreciation expenses will generally line up with its CapEx each year.

For a company with periodic large capital expenditures, we typically refer to its ‘EBITDA less CapEx.’

These sort of businesses often have a large amount of depreciation and so if we were to just look at EBITDA we would miss the large capital expenditures and the associated valuation would be meaningless.

And we use just EBITDA for companies that have only modest periodic capital expenditures such as in certain service businesses or distributors.

Neither EBIT nor EBITDA is better per se, they’re just more appropriate in different circumstances.

What is an EBITDA Bridge?

Another way we use EBITDA is to build an EBITDA bridge to allow us to see in more detail what is contributing to a company’s changes in cash flow from one period to the next.

The way to make a simple EBITDA bridge is as follows:

-

Step One: take a company’s revenue, gross profit margin, and SG&A costs from one period, say 2018, and strip out all of the interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization embedded in each of the cost of sales and SG&A, and then to do the same for another, similar length period, say 2019.

-

Step Two: Use the resulting adjusted gross profit % from the first period and multiply it by the difference in revenue.

That’s the amount of the EBITDA change attributable to the growth or reduction in revenue between the periods.

- Step Three: Then, take this figure and subtract it from the actual change in gross profit between the periods.

This is the amount of the EBITDA change that’s attributable to the change in the gross profit % between the periods.

- Step Four: Next, look at any changes to the amount of SG&A. That’s the amount of the EBITDA change that’s attributable to changes in the company’s overhead expenses.

Doing this for multiple periods in a row is a great way to see how a business is performing and adapting over time. Here is an example:

The Importance of EBITDA

In the end, EBITDA is just a quick way to think about the cash flow of a business.

But that’s why we use it so much; it allows us to quickly reference how a company is doing in relation to other firms.

When considering speaking about a potential acquisition, we might say: ‘This is a manufacturing business. It has 40 employees, a revenue of $7 million, and an EBITDA margin of $1.3 million. EBITDA has been relatively steady for the past few years, and no customer represents more than 5% of revenue. We’ve offered 5x EBITDA.’

Because of this, EBITDA is an important metric for any business owner to understand.

Whether you’re seriously considering selling or still exploring the idea, you’ll want to get a ballpark figure of what your business is worth. After calculating your EBITDA margin, visit our Business Valuation Calculator to get an estimate of what your business may be worth. It only takes 5 minutes and requires no further commitment on your part

P.S. Check out Warren Buffett's letters to shareholders for an entertaining sidebar on the topic of EBITDA & 2000 letter (page 16) and 2002 letter (page 20).