Senior debt, also commonly called a senior term loan, is a loan received from a traditional commercial bank that has a specified repayment schedule and either fixed or floating rate interest.

Through the years we have found that small company owners often don’t have a complete understanding of the types of financing sources used in a small company merger and acquisition transactions. As a result, we would like to do a small blog series to explain the various types of financing sources and address the related sentiments that “debt is bad” and “private equity firms always over leverage”.

In this post, we will be covering the following:

-

- Senior Term Loans

- Revolving Line of Credit

In general, there are three primary financing sources used in small company M&A transactions: traditional bank debt, mezzanine debt, and equity.

Traditional Bank Debt

We are going to start with traditional bank debt.

Hadley uses two forms of traditional, commercial debt when acquiring a small business: a senior term loan and a revolving line of credit.

Senior Term Loans

Senior debt, also commonly called a senior term loan, is a loan received from a traditional commercial bank that has a specified repayment schedule and either fixed or floating rate interest. Senior debt used in small company M&A transactions is most typically a cash flow-based term loan, which means that instead of lending against physical assets the bank is lending against a company's consistent cash flow (or EBITDA).

It is very common for banks to require personal guarantees from business owners when issuing senior term loans to a closely held, private company. These guarantees help protect the bank against the risk of loss associated with poor business performance.

Hadley is able to operate without personal guarantees.

The term (or duration) of a senior term cash flow loan is usually around 5 years.

The rate of interest for a cash flow term loan is typically higher than an asset based term loan but pricing depends on current market rates and the company's financial characteristics and performance.

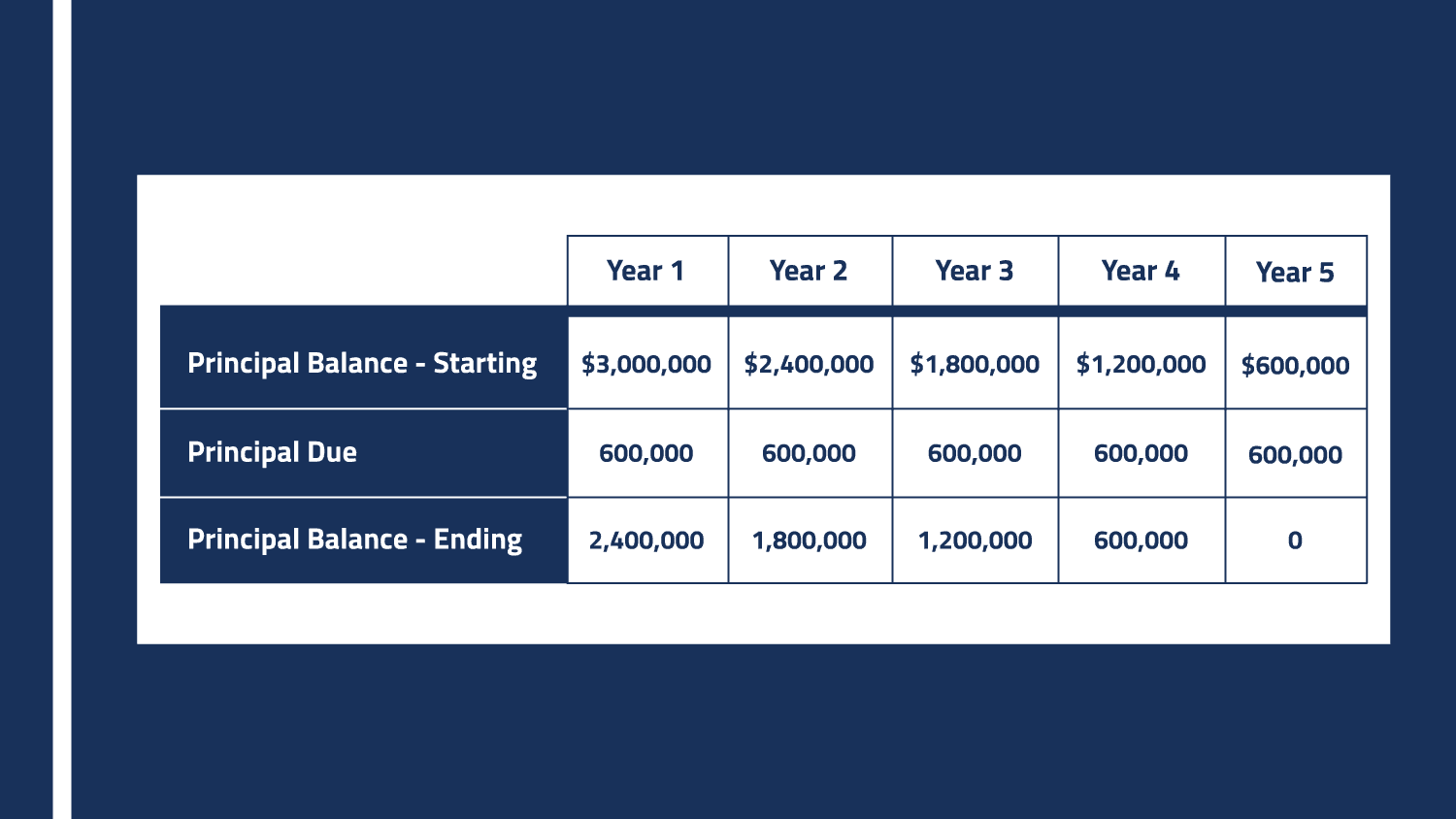

The principal on senior term loans is typically paid in equal monthly (or quarterly) installments over the term. For example here is a typical amortization schedule for a $3 million term loan with a 5 year term:

Revolving Lines of Credit

The second type of traditional commercial debt that is commonly used in small company M&A transactions is a revolving line of credit.

A revolving line of credit is an asset-based loan because the bank has a lien on the assets that support the line of credit. The two main assets that support a revolving line of credit are accounts receivable and inventory.

The amount of these assets on a company’s balance sheet dictate the size of the line of credit. The lien on the assets, and the relative ease to realize the lien, allow banks to lend the money at lower rates than cash flow term loans.

Revolving lines of credit tend to have a one year, renewable term. They are called “revolving” because a borrower will frequently borrow against and repay principal balances on a regular basis. Hence, the amount of credit extended or available “revolves” as borrowings and repayments are made.

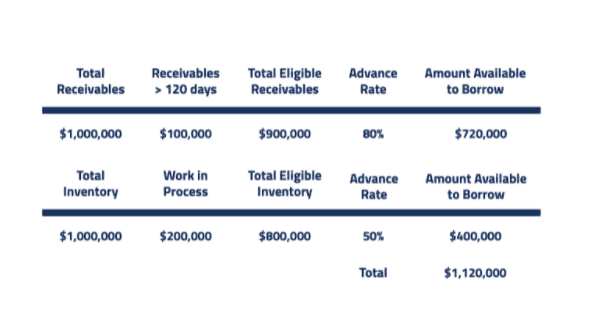

Banks protect themselves when issuing lines of credit by requiring borrowers to submit a borrowing base certificate. The borrowing base certificate determines how much money is available to a borrower on an asset-based revolving line of credit by 1) using advance rates and 2) excluding assets that cannot be turned into cash quickly.

Advance rates are the amount of money a bank will lend against the face value of an asset, Typical advance rates are 80% on Accounts Receivable and 50% on Inventory.

Excluding assets from a borrowing base means banks will not lend any money against the asset. A typical exclusion for Accounts Receivables is receivables that are 120 days past due. A typical exclusion for inventory is “work in process” inventory, meaning inventory that is between raw material and a finished good.

Below is a simplified version of a borrowing base certificate:

Debt is Bad vs. Debt is Good

Debt is not inherently good or bad. The perception of whether debt is bad or good is often related to risk tolerance and everyone’s tolerance for risk is different. However, regardless of one’s risk tolerance, it is important to recognize that debt can be an effective tool in small company M&A transactions.

Small company owners are frequently averse to any form of debt because they perceive it to be too risky. And, if the owner is required to personally guarantee the debt, as is frequently the case, this perception of (unacceptable) risk is valid.

In small company M&A transactions, debt financing provides a buyer with a source of low-cost financing that benefits the seller. How does a seller benefit from a buyer’s choice of financing? All else being equal, lower cost debt financing will increase a buyer’s return on equity. The higher expected return for a buyer, the more a buyer is willing to pay in an acquisition - to the benefit of the seller. Of course, too much of anything is generally not a good thing. Financing a transaction with 100% debt financing, if available, involves more risk (to the lender and the buyer) than a transaction using only 50% debt financing.

Private Equity Firms and Over Leveraging

This brings us to the conversation about private equity firms and their use of debt (or leverage) in leveraged buyout transactions. There is plenty of press about the use of debt by private equity firms - much of it focused on how private equity firms use ‘too much' debt, and invariably involves a story of the resulting failure of an acquired company. There are certainly private equity acquisitions that rely too heavily on debt financing and end poorly. However, the vast majority of private equity transactions use appropriate debt levels. An analysis of recent middle market leveraged buyout transactions shows Debt/EBITDA ratios of approximately 5.5x. While this debt/EBITDA ratio may be higher than a Hadley acquisition (more on this below), it could be appropriate in a middle market transaction. For context, middle market companies are those with enterprise values between $100 million and $500 million. These are larger companies that likely have deep management teams, robust systems, diverse sources of revenue and strong market positions. These characteristics may support higher amounts of debt than smaller, less developed companies.

How a Hadley Transaction Works

At Hadley, our choice of financing sources is designed to provide the business with enough flexibility to grow while optimizing its cost of capital. A typical Hadley transaction will utilize a senior term loan, a revolving line of credit, and equity. Compared to larger M&A transactions, we typically borrow senior debt that represents about twice a company's annual EBITDA (commonly described as 2.0x Debt/EBITDA). That is, if the target company has $1 million in annual EBITDA, we borrow $2 million in senior term debt. In finance lingo, this is called "2x senior leverage".

This amount of debt is much less than in larger transactions (and those transactions that show up in news stories). During strong economic times, large private equity acquisitions may use senior term debt of 7x Debt/EBITDA or more! Take, for instance, recent examples from SP Global and PE News.

Senior debt is an important source of financing in small company M&A transactions. When used appropriately, it has benefits to both buyer and seller. Determining the “right” amount of senior debt in a transaction is significantly dependent upon the circumstances of the business and the transaction and the risk appetite of the borrower.

Are you a small company owner that is evaluating a sale of your company but concerned about how a buyer like Hadley might use debt to finance the acquisition? If so, contact us today to start a conversation and get your questions answered.