Baskets and caps establish limits on the amount a buyer can claim against a seller for certain claims of indemnification.

An indemnification ‘cap' limits the overall liability of the seller to some dollar amount and an indemnification ‘basket' establishes a threshold under which the buyer cannot make a claim against the seller.

In this blog post, we are going to answer the following questions regarding indemnification in a small business acquisition:

- What are indemnification caps and how do they work?

- What are representations and warranties and how do they relate to indemnification?

- What are indemnification baskets and what types are common?

What are Indemnification Caps and How Do They Work?

In the legal documents for a small business acquisition, a seller will make certain representations regarding the business. You can read more about

The representations made by a seller are relied upon by the buyer and provide the buyer confidence in what they are buying.

A simple example would be that a seller represents that they own the assets they are selling to the buyer.

Indemnification baskets and caps are ways for sellers to establish limits on the amount a buyer can claim against representations made by a seller to a buyer.

An indemnification ‘basket' establishes a threshold under which dollar amount the buyer cannot make a claim against the seller, and an indemnification ‘cap' limits the overall liability of the seller to a maximum dollar amount.

Baskets and caps are just one part of the definitive legal agreements that formally document a transaction, but they're useful to understand.

What are Representations and Warranties and How Do They Relate to Indemnification?

Baskets and caps are a mechanism for buyers and sellers to establish dollar thresholds related to the representations and warranties made by a seller about the business.

The relationship between representations and warranties and indemnification baskets and caps can be confusing.

The paragraphs below provide a high-level summary of the relationships as well as a simple example.

Representations and Warranties: In the legal documents for a small business acquisition, a seller will make certain representations and warranties regarding the business.

For instance, the seller might represent that the business's inventory is of merchantable and usable condition.

If it turns out that some of the inventory is obsolete, the buyer might then have a claim against the seller.

Other representations concern the quality of the company’s financial statements, its compliance with laws, the conditions of its assets, its compliance with environmental and employment rules and regulations, etc.

The buyer and seller will then negotiate the ‘caps’ to these representations; that is, the maximum amount of money the buyer can recoup from the seller if it turns out that these representations are not accurate.

Indemnification Caps: Typically, small market transactions have caps equal to 50% of the purchase price.

However, such a cap will typically not apply to breaches of the seller’s representations under the purchase agreement, any losses due to fraud, or losses arising from certain ‘fundamental’ representations and warranties that are core the transaction, such as these:

- Organization and Good Standing: Seller is a company duly organized, validly existing and in good standing and has the full power and authority to own its property and carry on its business.

- Power, Ownership, Authorization and Validity: Seller and its owners have the right, power, legal capacity and authority to enter into this Agreement and perform all of their obligations under this Agreement.

- Title and Condition of Purchased Assets: Seller owns, free and clear of all liens, all of Seller’s real, personal, tangible, intangible, and other properties, rights and other assets of any kind.

- Intellectual Property: Seller owns all of the intellectual property used by Seller free and clear of any liens.

What are Indemnification Baskets and What Types are Common?

Indemnification Baskets: Many small market transactions also include a ‘basket’ of some kind.

A basket establishes a threshold under which the buyer cannot make a claim against the seller.

In small market transactions, the basket amount is usually in the range of $25,000-$50,000, and is often determined as a percentage of the purchase price (around 0.5%).

There are two primary types of baskets.

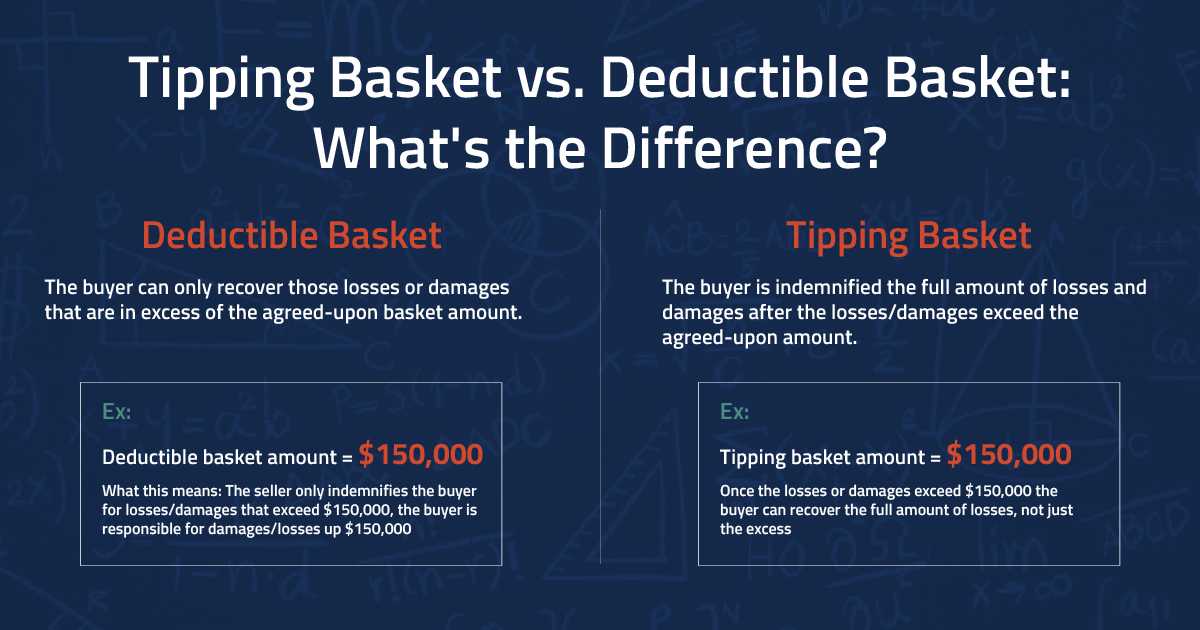

A ‘true basket’ (also sometimes called a ‘deductible basket’) means the seller cannot make a claim for indemnification until the total amount of losses exceeds the basket, and then only for the amount of loss in excess of the basket.

A ‘tipping basket’ (which is sometimes also referred to as a ‘threshold basket’) is a basket where if the losses equal or exceed the basket amount, the buyer will be entitled to full recover all of his or her losses, from the ‘first dollar.’

Thus, a ‘true basket’ is better for the seller and a ‘tipping basket’ is better for a buyer.

Example: Consider the case of a transaction with a purchase price of $5 million. A typical basket would be 0.5% of the purchase price of $25,000 and a typical cap would be $2.5 million or 50% of the purchase price.

Tipping basket vs. True basket: With a tipping basket of $25,000, if there were claims totaling $20,000, the buyer could not make a claim against the seller because the $25,000 threshold had not yet been reached.

But if the claims totaled $30,000 the buyer could make a claim from the first dollar, that is for the entire $30,000.

With a true basket of $25,000, if there were claims totaling $20,000, the buyer could also not make a claim against the seller because the $25,000 threshold had not yet been reached.

But if the claims totaled $30,000 the buyer could make a claim for the amount above the deductible of $25,000, or a claim for $5,000.

Indemnification caps: Continuing with our example, the seller of the business made a fundamental representation to the buyer that the seller owns all of the Seller’s assets free and clear of all liens.

After closing, a lien (or debt) is discovered by the buyer in the amount of $4 million.

In this case, the indemnification cap of $2.5 million does not apply because the seller breached a fundamental representation:

Title and Condition of Purchased Assets: Seller owns, free and clear of all liens, all of seller’s real, personal, tangible, intangible, and other properties, rights, and other assets of any kind.

In this case, the buyer can recover the entire $4 million from the seller due to the seller.

Alternatively, assume after closing, that the buyer determines that $3 million of the seller’s inventory is obsolete.

In this case, the buyer can pursue an indemnification claim up to the indemnification cap of $2.5 million and subject to the type of basket.

One Part of the Legal Agreements

Baskets and caps are useful to understand but they are just one part of the definitive legal agreements that formally document a transaction.

It is these documents in totality, versus just one part, that constitutes the total risk-sharing of the transaction.

That’s why it’s very important to have an experienced M&A attorney working on your transaction who can help negotiate these terms in a way that is fair to all parties and consistent with other similarly sized transactions.

Have more questions about baskets and caps in M&A?

Contact us today to set up a pressure-free call and learn more.