In the sale of a small company, the allocation of purchase price for tax purposes creates important considerations for sellers and it is important for sellers to have a basic understanding of how it works. Most small businesses in the U.S. are structured as S Corporations. Sellers of S Corporations are generally neutral to selling stock versus selling assets whereas buyers generally prefer acquiring assets. This topic is covered in greater detail in my colleague’s post: Asset Sale v. Stock Sale. For this reason, the majority of small company transactions are structured as asset acquisitions. An important consideration in a transaction structured as an asset sale is the purchase price allocation because it determines the sellers’ tax liability and the buyers’ tax basis in the acquired assets.

Purchase Price Allocation

Purchase price allocation is the process of assigning the purchase price of a business to the assets sold for the purposes of determining taxes owed by the seller and reporting the sale to the IRS.

Who is Responsible for Purchase Price Allocation?

The Internal Revenue Code requires that both buyers and sellers submit a purchase price allocation on form 8594. A common misconception is that buyers and sellers must submit consistent purchase price allocations.

However, if a buyer and seller submit contradicting purchase price allocations, the IRS may challenge one or both purchase price allocations. Therefore, it is best for buyers and sellers to agree on a purchase price allocation prior to closing. Most asset purchase agreements contain language requiring agreement on purchase price allocation.

What is the Fair Value of an Asset?

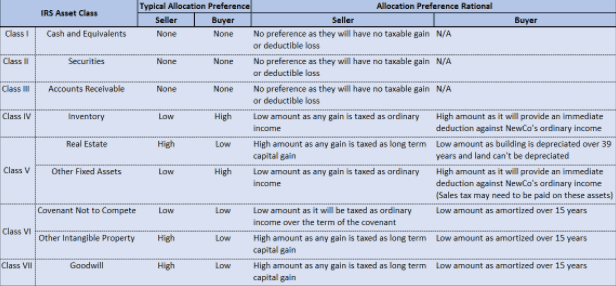

IRS Form 8594 defines seven asset classes to which the entire purchase price must be allocated. To comply with GAAP, buyers must allocate purchase price to assets based on their “fair value”. Fair Value is defined as “The price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.” For the lower and more liquid asset classes such as cash, securities, and accounts receivable, determining a fair value is straightforward as the values on sellers’ balance sheets usually reflect the assets’ fair values.

Less liquid hard assets such as property, plant, and equipment, often have a fair value different than the carrying value on sellers’ balance sheets. As such, buyers and sellers usually have an appraisal performed to determine the fair value of hard assets. I’ll cover this topic in greater detail in the depreciation recapture section of the post. The seven asset classes along with buyers’ and sellers’ typical allocation preferences are outlined briefly below.

How do You Allocate Purchase Price in an Asset Sale?

Purchase price allocation to the various asset classes above can have a major impact on the value received by both buyers and sellers in an acquisition. Sellers’ and buyers’ purchase price allocation preferences are typically at odds with each other. That is, purchase price allocation, for the most part, is a zero-sum game, any tax benefit gained by a seller will be lost by a buyer and vice versa.

Buyers prefer to allocate purchase price towards assets that can be deducted quickly against their New Company’s income. For example, buyers prefer fixed asset values to be as high as possible as they can depreciate the fixed assets over 5 or 7 years, two to three times faster than they would be able to amortize the alternative, goodwill. Sellers prefer to allocate purchase price towards asset classes that will be subject to capital gains tax treatment. Fortunately, under the required residual method asset classification is straightforward.

Residual Method

The residual method entails buyers and sellers placing a fair value on the assets being acquired and then allocating the purchase price to their respective asset class, with any remaining value allocated to goodwill.

The residual method requires that purchase price be allocated in the following manner:

- Reduce the purchase price by the amount of Class I assets (cash and equivalents) transferred from seller to buyer.

- Allocate the remaining purchase price to Class II assets (Securities), then to Class III (Accounts Receivable), IV (Inventory), V (Fixed Assets), and VI (Intangibles) assets in that order. Within each class, allocate the remaining purchase price to the class assets in proportion to their fair market values on the purchase date.

- Allocate any remaining purchase price to Class VII assets (Goodwill).

The amount allocated to an asset, other than a Class VII asset, cannot exceed its fair market value on the purchase date. If an asset in one of the classifications described above can be included in more than one class, it should be allocated to the lower numbered class (for example, if an asset could be included in Class III or IV, choose Class III).

Purchase Price Allocation Example

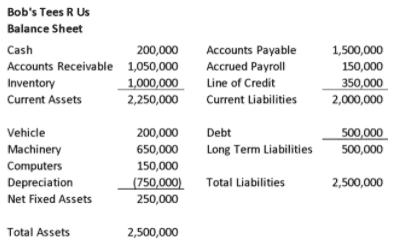

Let’s walk through an example using our hypothetical business, Bob’s Tees R Us. Bob’s Tees R Us is structured as a S Corporation and is being acquired by Hadley in a cash-free debt-free transaction. The only liability being acquired by Hadley is Bob’s accounts payable. All other liabilities, whether known or unknown, are being retained by Bob. Bob’s Tees R Us has the following balance sheet:

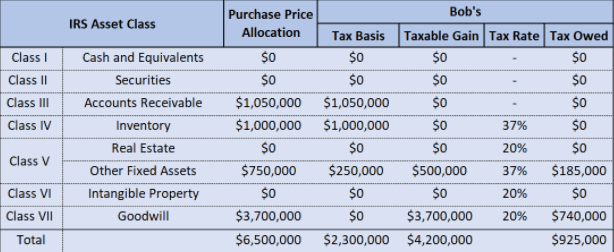

Bob has agreed to sell Bob’s Tees R Us to Hadley for $5.0 million: $4.0 million in cash plus a seller note of $1 million. Hadley and Bob hire a professional appraiser that appraises Bob’s fixed assets at a fair value of $750,000. Bob is in the highest marginal tax bracket. Bob and Hadley agree to the below purchase price allocation which results in Bob’s tax position being as follows:

Bob’s total tax due from the sale is $925,000. Outside of the favorably taxed goodwill, Bob pays the highest marginal rate on his fixed assets because the sale price exceeds his tax basis in the fixed assets. This outcome is due to a concept known as “depreciation recapture”.

Depreciation Recapture

Depreciation recapture is the difference between the sale price and the sellers’ tax basis in fixed assets. Depreciation recapture can occur in the sale of a business or if a company, in ordinary course, sells a depreciated fixed asset.

How is Depreciation Recapture Calculated?

Depreciation recapture in a purchase price allocation is calculated as the difference between the fair value of the sellers’ fixed assets and the carrying value of the sellers’ fixed assets. Sellers’ opinions on the “value” of their fixed assets often span a wide range, some may consider the book value and others may consider the used equipment market value or even the liquidation value. A professional appraisal should be performed to determine the true fair value of fixed assets for a purchase price allocation.

Sellers with large amounts of fixed assets that have been significantly depreciated, particularly those subject to accelerated depreciation, may be startled by the tax liability resulting from depreciation recapture. Let’s walk through an example to illustrate.

Depreciation Recapture Example

Bob’s brother, Tom, owns Tom’s Clubs R Us. Tom’s Clubs R Us has fixed assets that were purchased for $5 million. Based on the advice of his accountant, Tom used accelerated depreciation, particularly Section 179 deductions, to depreciate his fixed assets in order to lower his historical profits and related taxes. Tom’s fixed assets have a tax basis of $500,000. Tom has not read this post, so he doesn’t understand how purchase price allocation works.

Tom incorrectly assumes that only $500,000 should be allocated to fixed assets in a purchase price allocation because that is his carrying value for tax. As such, Tom expects that there will be no taxable gain on his fixed assets in a sale, with the balance of any gain being attributable to goodwill and taxed at capital gains rates.

Tom was unaware that the fair value of his fixed assets, not his tax basis, is used in purchase price allocation. The Buyer of Tom’s Clubs R Us hires a professional appraiser that determines that the fair value of Tom’s fixed assets is $4.5 million. The $4 million difference between $4.5 million and $500,000 is subject to depreciation recapture which is taxed as ordinary income. Under the current tax code, Tom’s long term capital gains are taxed at 20% and his ordinary income is taxed at 37%. In Tom’s case the “extra” 17% results in $680,000 of “additional tax” in the sale.

Tom complains to the Buyer that it’s unfair that he is stuck with the additional $680,000 of tax. The Buyer explains to Tom that his depreciation recapture tax bill is so large because he utilized accelerated depreciation to reduce his income taxes over the past several years. That is, Tom’s depreciation recapture is only a make-whole for the IRS. Tom is not really out-of-pocket an additional $680,000 because he received the same tax benefit in prior tax years.

The Value of Understanding Purchase Price Allocation

Purchase price allocation has major tax implications for sellers, which makes it important for sellers to have a basic understanding of how it works. This post provides the basic mechanics of purchase price allocation, but it is prudent for sellers to consult with tax accountants, M&A advisors, and attorneys when completing a purchase price allocation. Don’t end up like Tom with a surprise tax bill of $680,000 owed to Uncle Sam.

Thinking of selling your business? Contact Hadley Capital today to get a confidential valuation report.