Do you struggle to balance your business expenses and cash every month? Do your monthly expenses outweigh the cash your business brings in? If so, chances are your business is facing cash flow issues. You are not alone - studies show that nearly 61% of businesses struggle with cash flow problems.

What Is Cash Flow?

Cash flow is the amount of money that flows in and out of your business every month. Cash flow can be broken down into two components: cash receipts and disbursements. Cash receipts represent the flow of cash into your business, while cash disbursements represent the outflow of cash from your business. When your cash receipts are more than disbursements, your cash flow is positive. When your receipts are less than disbursements, your cash flow is negative.

Positive cash flow and negative cash flow are not inherently good or bad in any single period. Sustained positive cash flow is good, while sustained negative cash flow is bad.

Cash Flow Management and Why It Matters

Cash flow management refers to maintaining control over cash inflows and outflows. The primary goal of cash flow management is to effectively track the money coming into your business from sales against money going out of your business from bills, salaries, and other expenses. Cash flow management allows for a complete picture of how money travels through your business, making you more knowledgeable on the inner workings of your operations.

Cash flow management is vital because:

- It ensures your business always has an appropriate level of cash on hand to meet its obligations.

- It helps you to track the performance of your business and make necessary adjustments.

- It provides visibility into the appropriate timing and results of future investments.

Understanding the Main Cash Flow Levers

Cash flow levers are aspects of a business that can positively or negatively impact your cash flow. Below we have outlined some primary cash flow levers found in most businesses:

Inventory Lever

Inventories are the items a business uses in its operations to provide a good or service to a customer. Whether it be raw materials used in production, manufactured goods awaiting further processing, or imported goods soon to be distributed, all these things are considered inventory.

Inventory is an asset of a business. As inventory increases, cash decreases. As inventory decreases, cash increases.

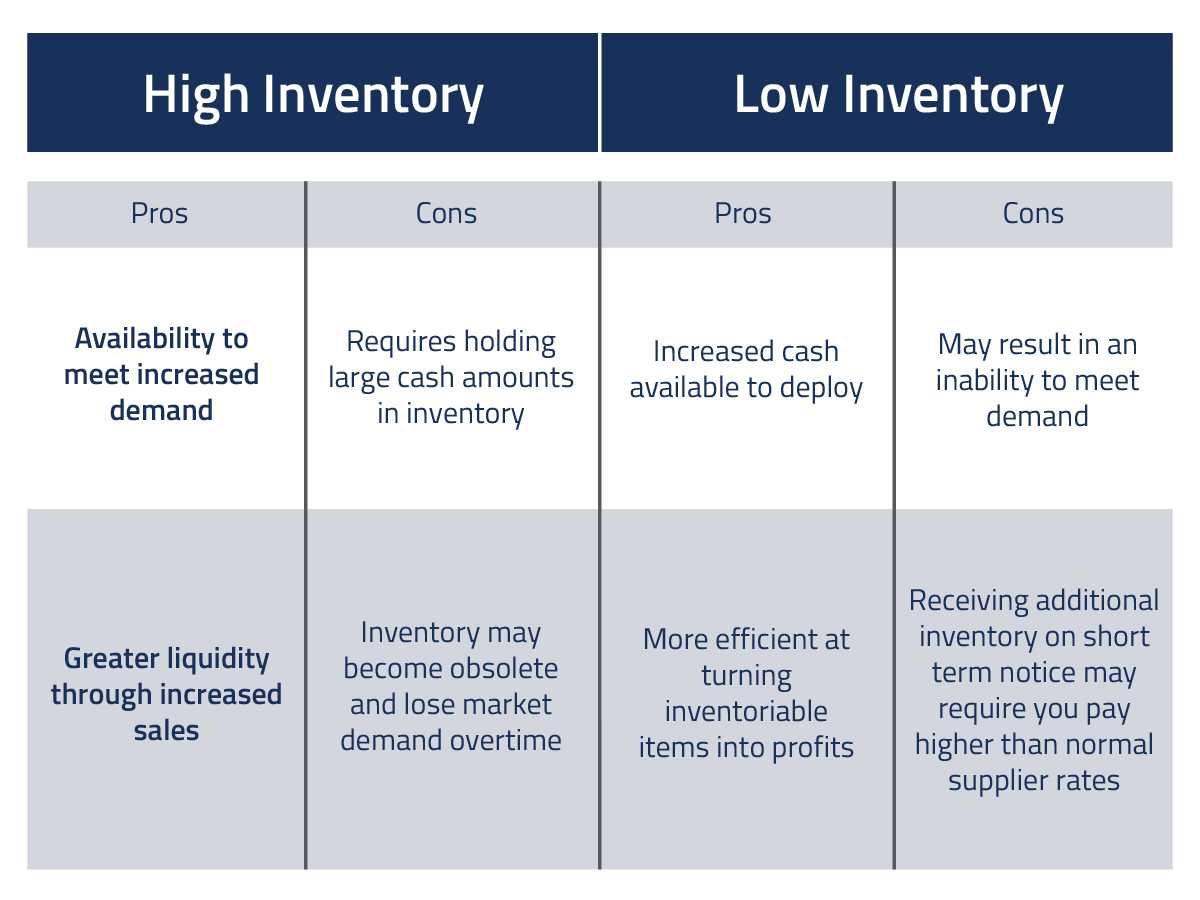

There are tradeoffs between having high levels of inventory and low levels of inventory.

Accounts Receivable Lever

Accounts receivable are payments from previous sales that are expected to be received by your business in the future. Accounts receivable are created when a business doesn’t receive immediate payment after providing a good or service to a customer.

Accounts Receivable are an asset of a business. When A/R increases, cash decreases. When A/R decreases, cash increases.

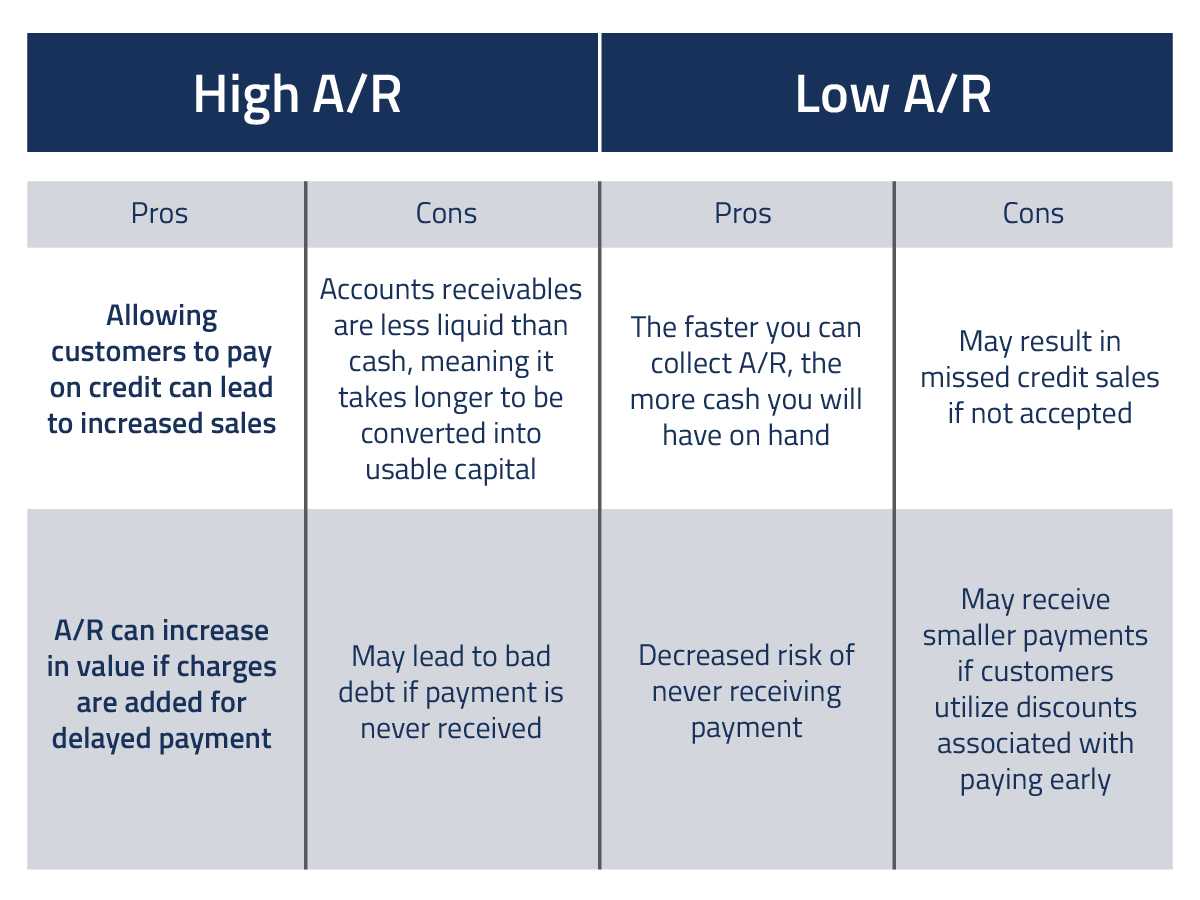

There are tradeoffs between having high levels of A/R and low levels of A/R.

Accounts Payable Lever

Accounts Payable are payments that are expected to be made by your business in the future. Accounts payable are created when a business buys supplies or inventory on credit.

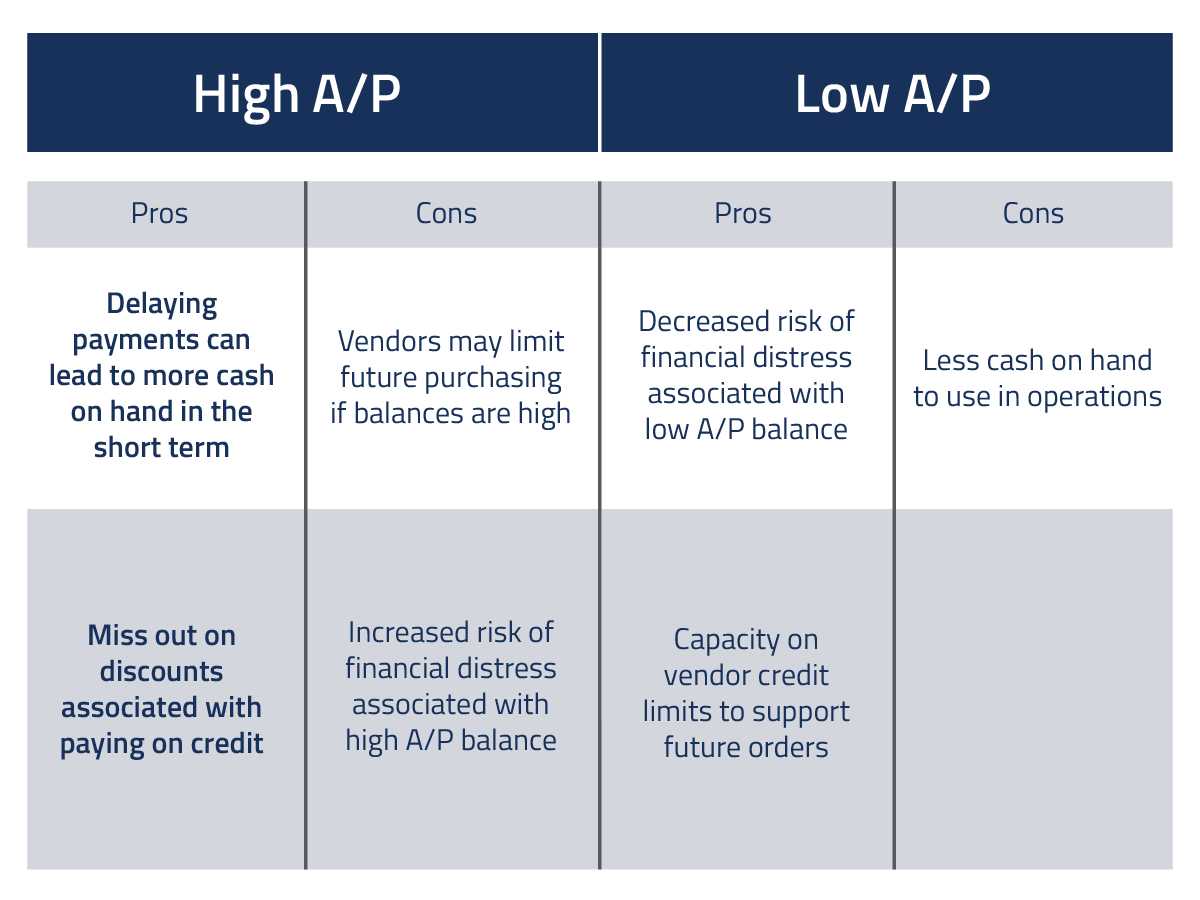

Accounts Payable are a liability of a business. As A/P increases, cash increases. As A/P decreases, cash decreases.

Expense Control Lever

Expenses represent the everyday costs of running a business and can include items such as payroll, rent, utilities, marketing, office supplies, among many others.

Maintaining tight control of expenses helps improve cash flow. When cash flow is tight, reducing expenses will improve cash flow.

Line Of Credit Lever

A line of credit is a loan from a bank that provides an amount of credit (usually called a limit) that is accessed as needed and typically repaid over time. Businesses use lines of credit to meet working capital needs and take advantage of strategic investment opportunities.

Lines of credit are an effective tool to provide stability in cash flow – when cash flow is low, a line of credit provides liquidity; when cash flow is high, the line of credit is repaid to provide liquidity for future periods of low cash flow.

Statement of Cash Flows

A statement of cash flows summarizes the amount of money coming into your company and the money going out. A statement of cash flows complements both the current period’s balance sheet and income statement.

How a Statement of Cash Flow Works

A cash flow statement is separated into three sets of activities in a business:

Cash Flow from Operating Activities

Operating activities within a Cash Flow Statement include the net result of profits minus expenses in any period, also commonly known as Net Income. Non-cash operating expenses such as depreciation and amortization are added back to Net Income. Operating activities also include changes in current asset and liability accounts from one reporting period to the next. Net Income + non-cash operating expenses + changes in current assets and liabilities = Cash flow from operating activities.

Cash Flow from Investing Activities

Investing activities within a Cash Flow Statement include any disbursements or receipts of cash due to any cash spent or received from the sale or purchase of fixed assets such as computers, equipment, vehicles, etc. Any investments made in non-operating assets, such as long-term financial investments, would also be reflected in the Cash Flow from investing activities.

Cash Flow from Financing Activities

Financing activities within a Cash Flow Statement include any receipts or disbursements of cash due to funding the business or returning value to shareholders. The two most common examples of financing activities are receiving and paying off loans from lenders, purchasing stock from shareholders, or paying dividends to shareholders.

The sum of Cash flow from Operating Activities +/- Cash flow from Investment Activities +/- Cash flow from Financing Activities represents cash created or used during the period. When added or subtracted to existing cash on hand at the beginning of the period, the result is cash on hand at the end of the period (which represents the cash account on the balance sheet for the period).

Using Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) To Understand Cash Flow Better

The cash conversion cycle is a calculation that measures how many days your business takes to convert inventory into cash from sales. CCC expresses how much time the business uses to sell inventory, collect money from customers (receivables), and pay its bills (accounts payable).

How to Calculate CCC

CCC has three main elements:

- Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO)

This is the number of days needed to change inventory into sold goods.

DIO = (Average Inventory ÷ Cost of Goods Sold) x 365

- Days Sales Outstanding (DSO)

This is the average number of days a business takes to receive payment for sales made on the account.

DSO = (Accounts Receivable ÷ Net Credit Sales) x 365

- Days Payable Outstanding (DPO)

This is the number of days a business uses to pay for products purchased from manufacturers or suppliers on the account.

DPO = Ending Accounts Payable ÷ (Cost of Goods Sold ÷ 365)

CCC = DSO + DIO - DPO

The Cash Conversion Cycle is a reliable metric that shows how a business manages working capital and how long cash is tied up in the business.

A lower CCC is better than a longer CCC.

Cash Conversion Cycle Example: Bob’s Tees

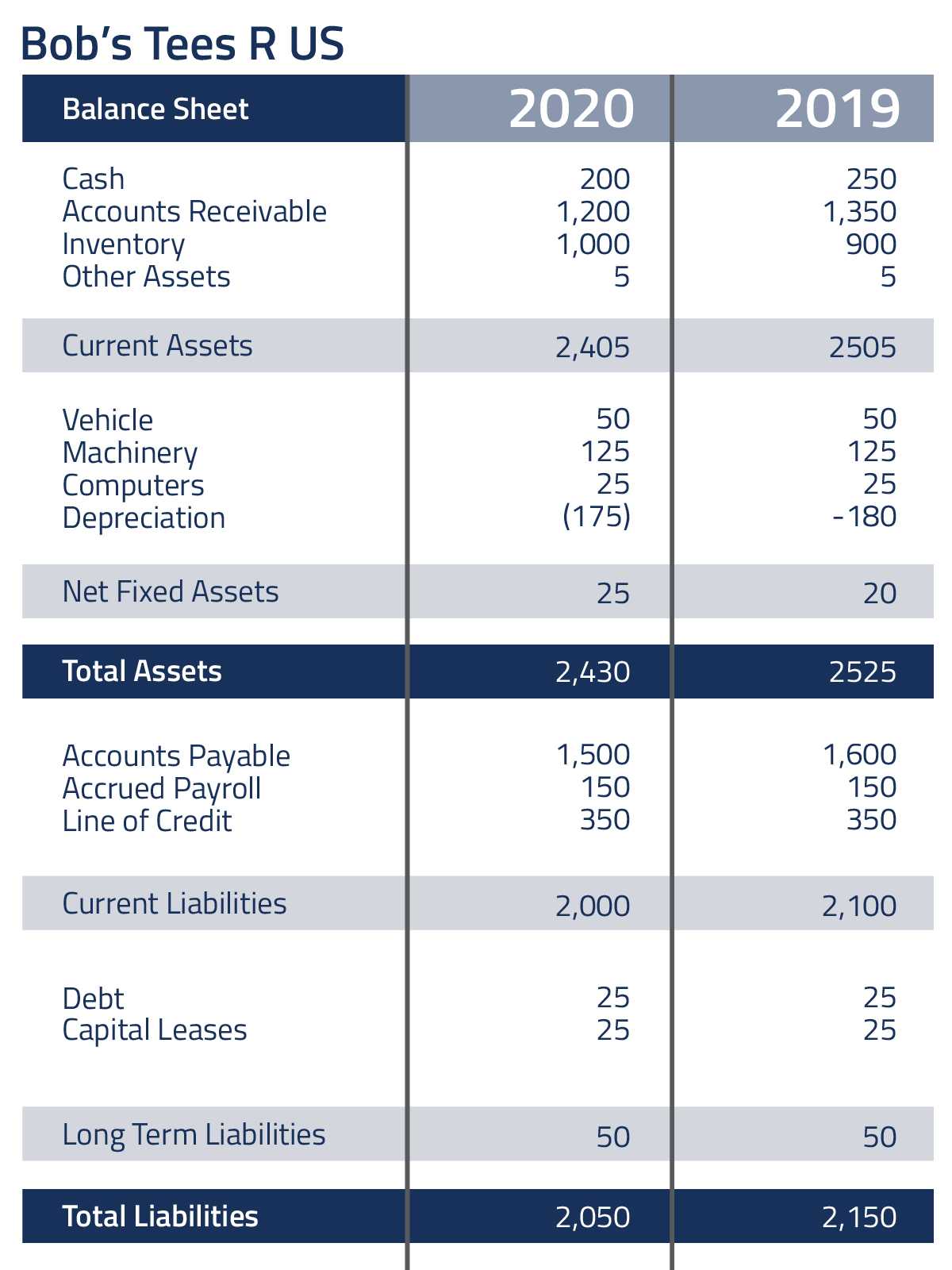

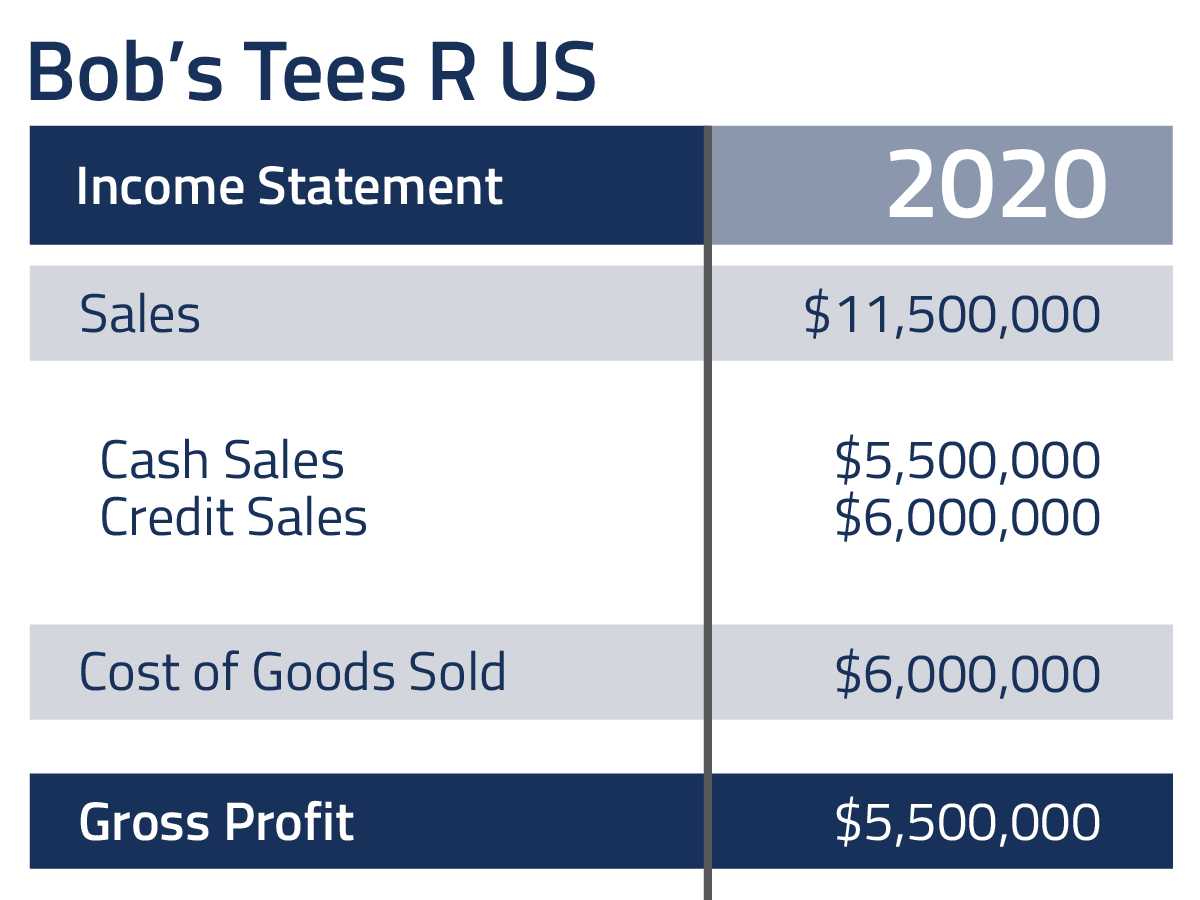

In one of our past blog posts about Asset-Based Valuations, we learned how to value a company’s assets by looking at a fictional business, Bob’s Tees R Us. Today we’ll revisit Bob’s Tees. However, this time, we will analyze the Cash Conversion Cycle.

· Finding Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO)

o DIO = (Average Inventory ÷ Cost of Goods Sold) x 365

§ =($800,000 ÷ $6,000,000) x 365

· It takes Bob’s Tees about 49 days to turn its inventory into sold goods.

· Finding Days Sales Outstanding (DSO)

o DSO = (Accounts Receivable ÷ Net Credit Sales) x 365

§ =($1,200,000 ÷ $6,000,000) x 365

· It takes Bob’s Tees about 73 days to receive payment for its sales made on account.

· Balance of sales are cash payments

· Finding Days Payable Outstanding (DPO)

o DPO = End Accounts Payable ÷ (Cost of Goods Sold ÷ 365)

§ =($1,500,000) ÷ ($6,000,000 ÷ 365)

· It takes Bob’s Tees about 91 days to pay for its purchases made on account.

· Putting it all Together

o CCC = DSO + DIO - DPO

§ = 73 + 49 – 91

· It takes Bob’s Tees about 31 days to turn inventory into cash flow from sales.

The 13-Week Cash Flow Statement

A 13-week cash flow is a cash management tool that forecasts the cash flow of your business for the next 13 weeks. The 13-week cash flow is a living document and is an update, in some cases, on a daily basis but, at a minimum, on a weekly basis. A 13-week cash flow can be used in distressed, high-growth, and steady-state situations.

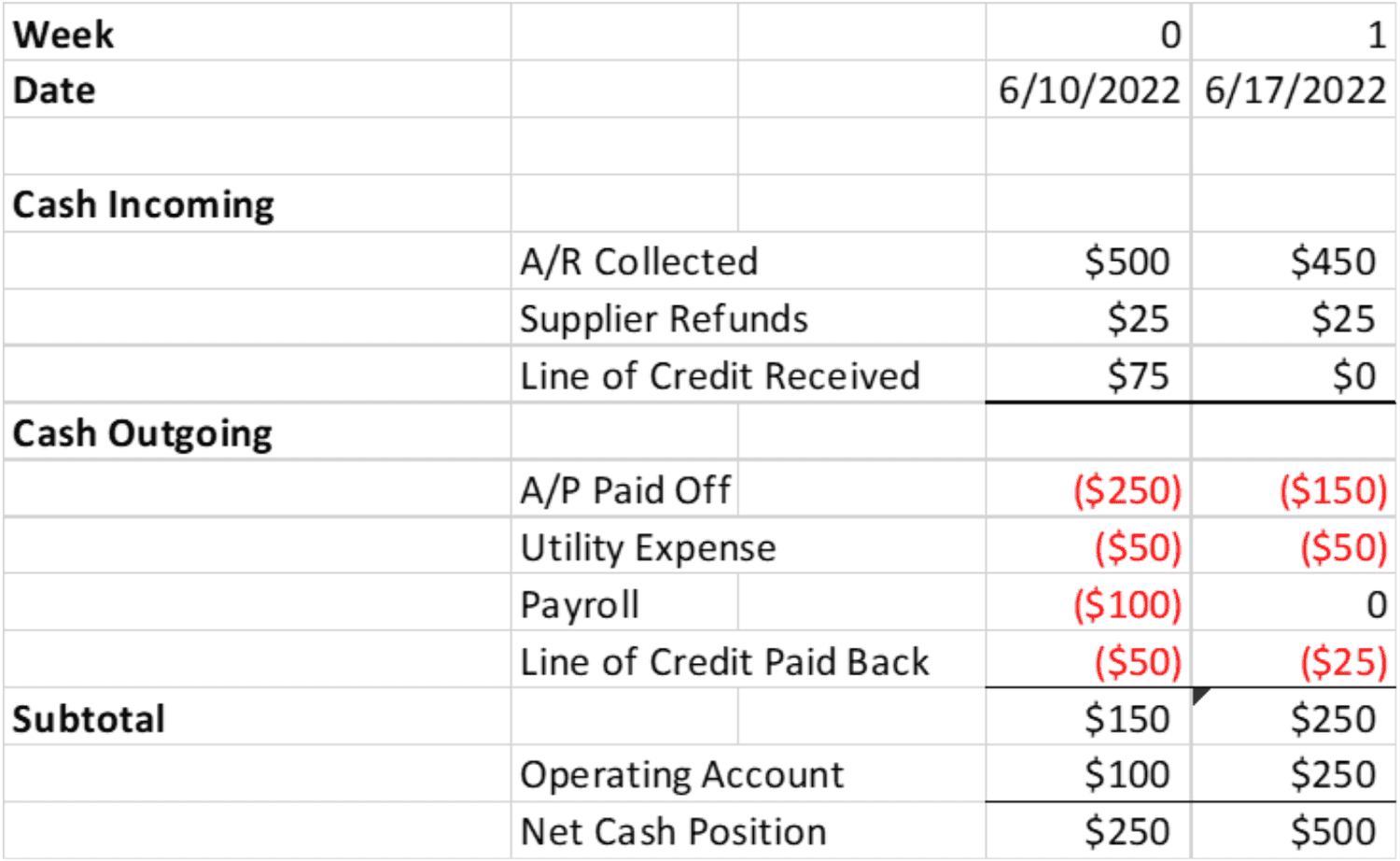

Example of 13-Week Statement, with basis week and first projected week

A 13-week cash flow statement has two primary components: cash coming into the business and cash going out of a business on a weekly basis. Examples of cash coming into a business include sales made, supplier refunds, or rebates. Examples of cash going out of a business include the cost of goods sold, utility expenses, and payroll. The timing of each inflow or outflow can be well understood (ex. timing of payroll) or less certain (ex. timing of customer payments). So, developing a 13-week cash flow involves some level of guesswork on timing and relies on business judgment.

The current week’s actual cash flow serves as the starting point for the 13-week cash flow. From that benchmark, you can project the coming 13 weeks of cash receipts and disbursements based on your business’s historical performance and future projections.

Use of 13-week cash flow in distressed situations:

- Ensure cash is available to meet operating needs

- Ensure sufficient cash to meet debt obligations

- To prioritize who gets paid and when they get paid

- To closely monitor the rate of collections of A/R

Use of 13-week cash flow in high-growth situations:

- To ensure cash is available to fund growth in A/R, inventory, and expenses

- To keep track of increasing accounts receivable balances and make sure you are on top of collections.

Use of 13-week cash flow in steady-state situations:

- To optimize cash flow

- To identify abnormal cash movements in the business

- To plan and prepare for lower cash periods or higher cash periods

Don’t Allow Cash Flow to Kill Your Business

Cash flow is the lifeline of any business. Effectively managing cash flow can seem like a daunting task but understanding the key levers of cash flow and tools to manage and improve cash flow will help any business at any stage of its lifecycle.

If you’re curious about how your cash flow is affecting your business’s worth or ready to take more serious steps toward working with an investor to help your business grow, contact us today for a pressure-free consultation.